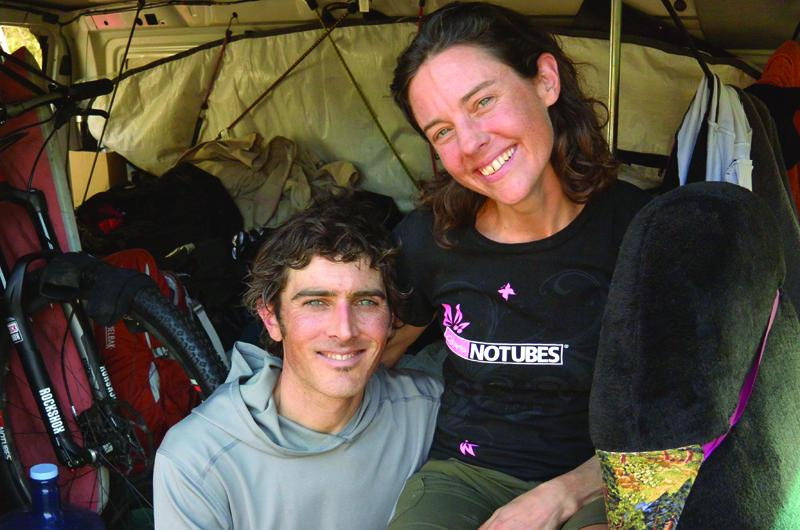

Mary McConneloug, forty-four, and Mike Broderick, forty-three, seem like normal people. At their home in Chilmark on a cold off-season evening, the couple appears to be like most couples getting ready for dinner. McConneloug makes soup, while Broderick sits nearby in his slippers. There is a bottle of wine on the table and a cozy warmth flows from the kitchen. Broderick looks wiry and in shape, but not overly so. McConneloug looks wholesome, like a baker or a seamstress, which she was for a time. There are no visible scars nor haunted looks of the hyper-competitive on either of them.

But Broderick and McConneloug are very far from a normal married couple. While it may seem odd that David Weagle, one of the top engineers in the mountain biking world, calls Martha’s Vineyard home, consider the careers of Broderick and McConneloug of Chilmark, without a doubt the most successful couple in mountain biking history.

McConneloug is a two-time Olympian, placing ninth in Athens in 2004 and seventh in Beijing in 2008. Both Broderick and McConneloug have represented the United States at the world championships for thirteen consecutive years. And here’s the kicker: while both are now in their forties they are still at the top of their sport, veritable dinosaurs who started out just when the sport was gaining traction, but by no means outclassed now by younger, stronger competition. In December, McConneloug was even named to the mountain bike long team for the 2016 Olympics in Rio. Of the eight women selected, up to two will be named to the final Olympic team in June.

Earlier in the day, before the soup and the wine and the soft evening lighting, both Broderick and McConneloug had completed five-hour training rides around the Island, something they do every single day of the year wherever they happen to be. About three-quarters of the year they spend traveling the world to different races. They also pile on the cross-training – surfing, stretching, yoga, paddle boarding, balancing, whatever they can come up with to keep their bodies functioning at their highest levels, while also remaining intact.

Here’s how Broderick describes a typical cross-country mountain biking race: “You suffer for an hour and a half like you can’t imagine, and when you go across the line you might have double leg cramps, you’re vomiting. It’s a beast of a day.”

But this story truly begins, as all biking stories usually do, with that first moment when the bike is encountered. At that moment it is not a path to glory or life’s enduring passion. It’s about being a little kid, and those two wheels mean pure freedom.

Broderick grew up on the Island, in the very house he now lives in with McConneloug. “I had a pile of junk bikes that we got from the dump,” Broderick remembered. “And I made bikes. I got a five-speed women’s bike that could rip. I would roll to Menemsha, two miles downhill, and it was my freedom. It was a great social environment down there. I worked at The Bite and just rolled down there and back.”

Broderick’s father, Steve, was an engineer and he put his four boys through college by starting an ice making business called Blizzard Brothers Ice. This was in the early 1990s; Broderick graduated from the regional high school in 1991. They sold ice to all the weddings, at the docks, to restaurants, and grew a successful business out of local, artisanal ice before that was even a term.

In those days mountain biking was still in its infancy and mostly a West Coast thing. But while attending Springfield College, Broderick began drifting away from “stick and ball sports” to mountain biking.

“I felt that feeling in the tires and the dirt, and it was something that I was hooked on right away. I would go wherever I could, bike paths, dirt roads, in my lifetime I remember Waskosim’s Rock always being there for me.”

But for a while, biking was still just one of his many sporting passions. After college he embraced the Vineyard way of life, working like crazy during the summer to save enough money to travel the world, spending four or five months snowboarding in addition to biking. This all changed when he met McConneloug.

“When I met Mary I saw an opportunity and said I should stop all this other stuff and take this base and focus it all on the bike. And it worked.”

McConneloug grew up in Fairfax, California, which many pinpoint as the birthplace of mountain biking in the United States. Mount Tamalpais in Marin County is close by, and today is still one of the most revered spots for anyone on two wheels. Those using two feet – some call them hikers – are not so pleased.

“There’s too many rats and not enough cheese,” Broderick explained about the prevalence of mountain bikers in that area. “There’s violence on the trails, booby traps in the worst cases,” he continued, referring to how some hikers try to take back the trails from the bikers.

McConneloug started riding a bike to school at the age of six, but didn’t ride her first mountain bike until she was thirteen. “It was just the new thing in town, with gears, no shocks or suspension,” she remembered. When mountain biking became an Olympic sport in 1996 in Atlanta, she still wasn’t into it. But then she moved to Oregon and those knobby tires began to gain traction in her life.

“I said I’m going to race bikes and be a seamstress. Just whatever, let’s try it. And that’s exactly what I did. And I supported myself at a rock [climbing] company as the head seamstress designing clothes and then racing my mountain bike on the weekends. It became my passion. I just fell in love with it, it was the ultimate challenge.”

Broderick and McConneloug met at a race out West, naturally, and then by coincidence Broderick showed up in McConneloug’s hometown a few days later and they ran into each other at the local hardware store. At least that’s the way McConneloug tells it.

“There might have been a slight stalking element there,” Broderick admitted. He used the cover of a race in the area to explain his reasons for being at that hardware store on

that day and at that moment. And it worked.

The two became a team, essentially spending all day, every day racing mountain bikes. Here’s how they remember the early days.

“I had a Volkswagen bus when I met Mike and he had a Toyota truck,” said she.

“We’d stuff it with equipment, park, open the doors, and tumble out and camp there,” said he.

“We did the whole national series, which are five or six events throughout the season from May through September, say.”

“Thirty to fifty races a year. Some of those are six-day events, some are one day. Sometimes we raced twice in a weekend.”

“For a couple of years we threw everything we had into it.”

“I went into debt with credit cards.”

“We didn’t have a mortgage. We didn’t have children. I was just living my life as I wanted to. We lived here for part of it, we lived out West.”

“It was an investment. I knew Mary had so much talent it was just a matter of time.”

Broderick was right. McConneloug made the Olympic team at the age of thirty-three, just four years after she started taking the sport seriously. To prepare for her first Olympics, the two lived in an RV and car-camped for eight months throughout Europe, racing every weekend. And that’s still how they roll, stowing all their equipment in an RV and traveling the world for most of the year, racing wherever they can. In January they headed to Chile, down near Patagonia, for the Trans Andes Challenge.

“We kind of migrate there lately in the winters for the past six years,” said McConneloug. “It’s summer there then and the biking is fantastic.”

“They are going through a mountain biking revolution,” added Broderick. “The event we do is a six-day mountain bike race. The Chilean government pays money for it because it’s so important for the economy.”

The two inspire and feed off each other’s passions, which is how they’ve been able to stay competitive for so many years in a sport that grinds away at the body. They are their own coaches, mechanic (that’s Broderick), travel agents, trainers, and nutritionists. And that’s the way they like it, with no one to answer to but themselves.

“To have a team that tight, that understands exactly what’s going on. To say, ‘Christmas, what’s that? Let’s go train,’” said McConneloug. “It’s pretty rare to find two people who are that into the same rigorous sport and are able to manage it the way that we do.”

“We kind of just wake up and start talking about how to get faster every morning,” Broderick said.

And they also have their secret weapon: the Vineyard.

“You come here and you get on the ferry and you’re just packed away on the Island,” said McConneloug. “This is the restorative place.”

While on the Vineyard they ride every day, but try to stay low-key in general and especially with regard to mountain biking here. Out in the world they relish the role of being ambassadors to the sport, bringing help to local economies around the world and inspiring people to just get on a bike, at any age. But while mountain biking destinations like Moab, Utah didn’t really have a wide range of activities to attract visitors before the bikers discovered that desert paradise, Martha’s Vineyard, they feel, has plenty of other attractions.

Plus, they worry about the toll mountain biking would take on the Vineyard if bikers in large numbers were to descend upon the Island. “Martha’s Vineyard is one of the most fragile environments I’ve ever seen for cycling. It’s just sand,” Broderick said.

That being said, they admit it’s a great place to bike off-road. “You could just park somewhere in the middle and piece together a ride,” McConneloug said. “You could ride for hours.”

Which is what they do, sometimes heading out with David Weagle, completing the loop of mountain biking royalty hidden away here on the Island.

“He is so talented,” Broderick said. “And he also has a certain way of breaking it down that is so simple. It seems so simple when I’m talking to him and he’s like, ‘I just designed this computer program to design this thing,’ and it all comes out as if it’s casual, but the level he’s at is astonishing. And the stuff he’s putting out is second to none. He is definitely the man.”

Looking into the future, the two see the Olympics, hopefully, on the horizon. They also see plenty more racing despite their ages. “They say you turn diesel when you get older,” McConneloug said. But perhaps what they are most excited about is inspiring others to get on a bike.

“I saw a high school kid today out in the woods, just happened to pass him when I hit the most critical section of Waskosim’s Rock, and I announced I was there,” Broderick said. “He was with his family and he was like, ‘Hey, cool bike that looks really hard.’ And then I came around the corner and there’s a staircase you could ride and I know he could see me and I just hit it with everything and launched over this staircase and I could hear him hollering, ‘Oh man, that was sick!’ He’s going to get his bike out right now. I’m sure of it.”