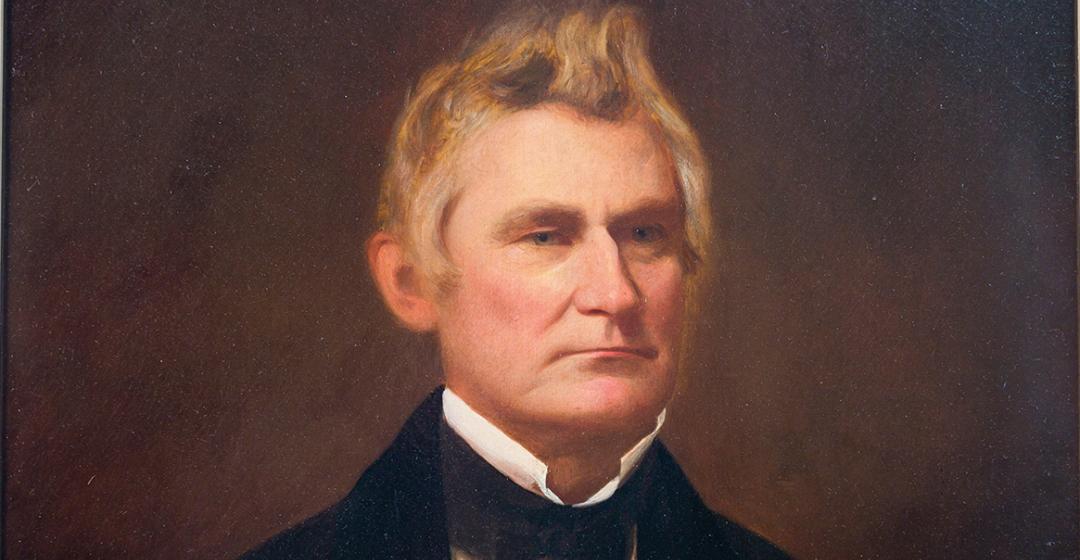

“Tycoon” is an old-fashioned moniker, out of place in our digital century. It would seem as incongruous on Bill Gates or Mark Zuckerberg – our Carnegie and Vanderbilt – as muttonchop whiskers and silk top hats. Yet for Dr. Daniel Fisher, the whale oil king of nineteenth-century Edgartown, no other title will do. No individual played a larger role in the Vineyard’s whaling industry, and – though he never wielded a harpoon, or went to sea except on a ferry – nobody made more money from it.

Fisher was born with the century: June 19, 1800, in Sharon, Massachusetts. Despite references to him coming from poverty, his parents – Owen and Betsey Fisher – appear to have been solidly middle class, possibly more than that. They had, in any event, the money to send young Fisher to a preparatory school in Dedham, where he spent what he later described, in a letter to one of his sons, as “the happiest days of my life.” It would be easy to write such sentiments off as conventional piety – the kind of thing that parents say to children because it is expected – but in Fisher’s case it seems to have been true. He kept several of his boyhood schoolbooks for the rest of his life, and after his death they passed to his daughters, and ultimately to the Martha’s Vineyard Museum.

Fisher’s happiness was apparently matched by diligence, and after completing his studies in Dedham he enrolled at Brown University. The university consisted, in those days, of a single thirty-year-old brick building on a hilltop overlooking Providence, but its reputation – then as now – stood just slightly behind those of Harvard and Yale universities. A contemporary of Fisher’s remembered the professors as “portly men, going on to sixty” who walked with silver-headed canes and sat cross-legged in upholstered armchairs, demanding word-for-word repetitions of the texts their students had been set to study. The curriculum included mathematics, geography, philosophy, and elocution, along with Greek and Latin courses in which “everything depended on translation, generally guessed out, often stolen.”

Like its rivals, however, Brown was also experimenting with education in the natural sciences – chemistry, mineralogy, and botany – and had established a medical school in 1811. It was this side of Brown that evidently stirred Fisher’s passions. A newly graduated member of the class of 1821, he headed north to Massachusetts and enrolled at Harvard Medical School. Formal medical education was the exception, rather than the rule, in the 1820s. Learning the field through apprenticeship to an experienced physician was not only possible, but commonplace. Fisher’s choice of Harvard – a more expensive pathway to an MD, but also a more rigorous and comprehensive one – made a statement: he was a young man of means and ambition, determined to make a mark on the world.

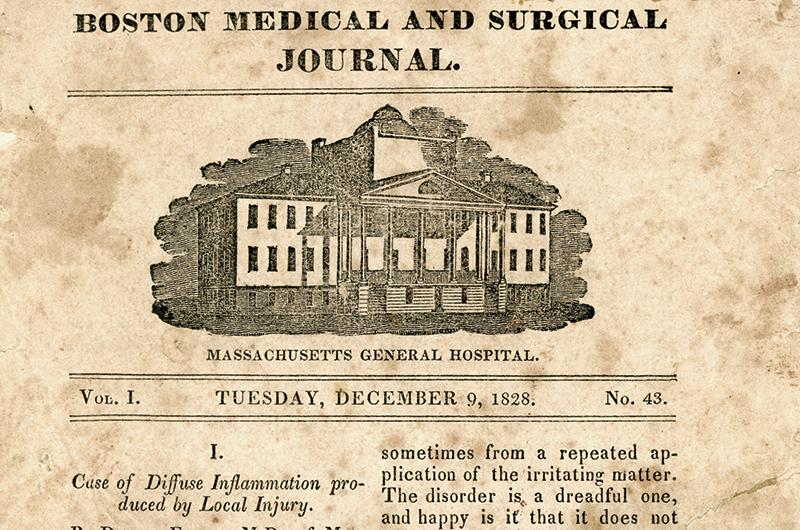

Harvard Medical School in the early 1820s was a good place to be ambitious. Fisher’s years there brought him into the orbit of Dr. John Collins Warren, one of the most accomplished physicians and surgeons of his generation. Educated at the University of Edinburgh and at hospitals in Paris and London, Warren was a relentless innovator. He cofounded The New England Journal of Medicine in 1812 and Massachusetts General Hospital in 1821, and served as the first dean of the Harvard Medical School from 1816 to 1819. Fisher studied under Warren first at Harvard Medical and then, after receiving his MD in 1825, during an internship at Mass General. When Fisher came to the Vineyard, he was not just a trained doctor but as well-trained a doctor as it was possible to be in the late 1820s.

Fisher, not yet thirty and not yet married, could have established a practice virtually anywhere he chose. In 1826, he chose Martha’s Vineyard, accepting an appointment from the U.S. Collector of Customs in Edgartown to provide medical care to sick and injured sailors at the Marine Hospital in Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven). The “hospital” was notional. It was not – and would not be – a dedicated building until 1879 when an abandoned lighthouse at the head of Holmes Hole Harbor was appropriated for the purpose. Fisher was agreeing to provide the required care in his home, “boarding out” convalescing sailors elsewhere, as needed, in exchange for an annual stipend from the government. The Marine Hospital system was an early example of what would today be called the social “safety net.” It was funded by a dedicated fee paid by ship owners, along with customs, duties against the day when their sailors might need medical care far from home. The stipend – a guaranteed income, reliably paid by a federal agency – represented an attractive supplement to a small-town doctor’s regular fees for service. Neither the $95-a-year stipend nor the fees, however, represented a road to real wealth. Small-town doctors in early-nineteenth-century America were respected, even beloved, by those they served, but few got rich at it.

Fisher’s early years on the Island were spent in Tisbury. He is listed as a resident of that town in a document dated January 16, 1828: a bill of sale recording Fisher’s purchase of 1/16 interest in the cargo schooner Hiram from mariner (and future Cape Pogue lighthouse keeper) Lot Norton. His next recorded investment, in October 1828, was more ambitious: a share of the Edgartown whaler Meridian. She sailed that month for the Pacific and returned a little less than three years later with 3,000 barrels of sperm whale oil.

All whale oil was valuable, but sperm oil – which burned with a bright, smokeless flame and lubricated fine mechanisms such as clockworks without gumming them up – was the most prized of all. The United States Lighthouse Establishment, which used tens of thousands of gallons annually to fuel its beacons, was paying 62 cents a gallon that year. Other buyers, unable to leverage the same kind of quantity discount, would have paid more. Even at government prices, however, the cargo of the Meridian was worth a small fortune: $84,000 – the equivalent of $2.2 million today. Fisher’s share of the profits was the first money he is known to have earned in the whaling business. It would not be the last.

In December 1828, as the Meridian worked her way down the South American coast toward Cape Horn, an article by Fisher on the “Cause of Diffuse Inflammation Produced by Local Injury” appeared in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (the forerunner of The New England Journal of Medicine). On September 16, 1829, as Meridian cruised the Pacific in search of whales, he exchanged wedding vows with Grace Cousen Coffin – or Cousens Coffin; the records are inconsistent – a member of one of Edgartown’s oldest and most respected families.

Fisher was thirty years old in April 1831, the month that Meridian’s bonanza of sperm oil was unloaded onto Osborn’s Wharf at the foot of Main Street in Edgartown (now the site of the Edgartown Yacht Club). He was a year-and-a-half married, living with his in-laws, and Grace was pregnant with their second child. No letters or diary survive to record his thoughts, but it is not difficult to imagine what they were. His ship had literally and figuratively come in, and the money he had “cast upon the waters” during his first year on the Island had been returned in abundance. He was, if not yet wealthy, far more comfortable than he had been. He had options, and he exercised them in a way that would change the course of his life: he bought land.

A less ambitious man, or a more conventional one, might have set his sights on an empty lot where he could build his expanding family a home of their own. Fisher, however, was playing the long game. On September 23, 1831, he and two partners – Ichabod Norton and Charles Smith – paid widow Hannah Norton $420 for “one half of a dwelling house…and the whole of a shop…together with a Lot of Land adjoining said dwelling house.” On October 6, the same three men bought “a parcel of upland and meadow” on the harborfront for an additional $54. Six weeks later, on November 17, they paid $500 for a third parcel adjoining the first two. The details of these transactions, recorded in the Dukes County Land Records, are both financially and geographically complex, but the intention is clear: Fisher and his partners were buying up small parcels of the Edgartown waterfront in order to create a single large one that would be more versatile and more valuable.

Whaling is an industry built around the extraction and processing of natural resources. Whaleships were specialized seagoing factories, designed to efficiently turn a fifty-ton whale into neat salable packages. Every specialized piece of equipment they carried was designed to expedite that process, and profits were shared among the members of the crew according to the value, and rarity, of the skills they brought to it. Ordinary seamen who pulled oars and chopped blubber earned less than harpooners, but also less than the ship’s cooper: the man who built the all-important barrels that brought the oil safely to market. The Edgartown waterfront was, in a similar way, optimized to meet the needs of the ships. It was lined with workshops and stores capable of producing, supplying, or repairing everything a whaleship needed, and warehouses to store and protect their cargoes. Whalers (ships or men) earned money only when they were at sea. Time in port was time wasted, and the Edgartown waterfront was designed to make the turnarounds between voyages as efficient as possible.

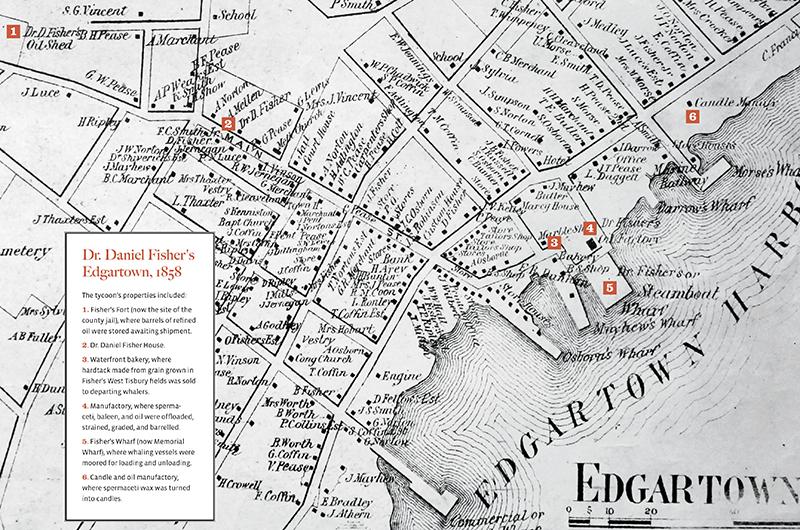

Sixteen land transactions in the eleven years between 1829 and 1840 – eleven purchases, four sales, and a gift – left Fisher in control of a substantial part of that waterfront. His holdings included what is now Edgartown Memorial Wharf, along with land north and south of it, bounded by North Water Street to the west and Edgartown Harbor to the east. In addition to the wharf – one of five in Edgartown – his waterfront business interests included a store, a bakery, and an “oil and candle manufactory,” along with unspecified other buildings that may have been storage sheds or warehouses. Property values had risen over his decade of wheeling and dealing, and the size of his transactions rose with them. At the beginning of the decade he had spent $400 and $500 at a time; by the end of it, he was spending ten times that. Along the way, however, he acquired what Edgartown historian Elizabeth Villard describes as “an all-purpose whaling center.”

Like the Rotch family in New Bedford, Fisher pursued “vertical integration” decades before Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford made the strategy (in)famous. Whaleship owners who paid to moor their vessels at Fisher’s Wharf while preparing it for the next voyage found his bakery ready to supply them with hardtack, the durable (if unappetizing) bread that was a staple of nineteenth-century sailors’ diets, and other Fisher-owned businesses ready to meet other pre-voyage needs. When ships returned at the end of a successful voyage, and paid Fisher for the right to unload at his wharf, they found him ready to offer them (and, doubtless, owners whose ships tied up at other wharves) a price for their cargo. The whale products he bought could be processed into salable commodities almost literally on the spot, since his “manufactory” was only yards away. The speed and convenience must have particularly appealed to captains and crews from Nantucket, who – barred from their own harbor by a sandbar that a fully laden whaling ship could not cross – were often directed by shipowners to unload in Edgartown, almost within sight of homes they had not seen for three or four years.

Whaling ships routinely brought home three different products: whale oil, spermaceti, and baleen (called “whalebone” even though it was actually made of tough, flexible keratin, like fingernails). Fisher’s dockside factory handled the first two. Whale oil was rendered from the blubber of the whale in iron kettles while the ship was still at sea, then cooled and poured into barrels for storage. Spermaceti, a waxy liquid found in the head cavities of sperm whales, was bailed directly into barrels and processed ashore. Possessing the texture (and, it’s said, the smell) of raw milk in its natural in-whale state, it begins to solidify when exposed to air and cold. Onshore processing was a multistep operation – freezing, heating, and multiple rounds of pressing and filtering – designed to separate spermaceti into its components: oily liquids and waxy solids. The first pressing produced the highest grade of sperm oil, called “winter oil” because it remained liquid in all but the most extreme low temperatures. The “spring oil” and “summer oil” produced by later pressings were of lower quality and commanded lower prices, though all of it sold for more than ordinary “whale oil” derived from blubber. The leftovers of the process were a brown, waxy solid known as spermaceti wax.

The workers in Fisher’s waterfront oil and candle operation spent their days immersed in those processes. Barrels of ship-processed whale oil and raw spermaceti entered, and barrels of filtered, graded whale oil and sperm oil emerged, carefully repacked and labeled for sale. The spermaceti wax – melted and bleached white – was turned (still on the premises) into spermaceti candles. The candles, like the sperm oil of which their wax was a byproduct, were prized for their bright, nearly smokeless flame. They were a premium product and commanded a premium price. Burning spermaceti candles rather than beeswax (let alone tallow) ones, and burning sperm oil rather than whale oil in lamps, was a symbol of wealth and refinement.

Fisher’s waterfront holdings assured him of a steady stream of income – his spermaceti candle factory was said to be the largest in the country at the time – but they were not his only business ventures. He also acquired, between 1829 and 1840, parcels of land in three other areas of Edgartown: along the road to Holmes Hole (now the Edgartown–Vineyard Haven Road) and the “road to the mill” (now the Edgartown–West Tisbury Road), and on the “Great Plains” near Edgartown Great Pond and Katama Bay. These purchases, like his first purchases along the waterfront, were not necessarily for immediate use but part of a larger plan. The land on the Great Plains may have been a first step toward involvement in Edgartown’s lucrative herring fishery. The other plots may have offered access to woodlots (to fuel the ovens of his bakery and the kettles of his oil factory) or merely farmland intended for resale when their value had risen.

The most visible parcel of land that Fisher acquired in the eleven tumultuous years between 1829 and 1840 was, however, not a purchase but a gift. A prime parcel at the head of Main Street, adjacent to the site of the soon-to-be-built Whaling Church and two doors from the modest wood Dukes County Courthouse, it was a benefaction from Allen Coffin, the father of Fisher’s wife, Grace. The deed formally transferred the lot to Fisher, but its wording left no doubt of Coffin’s intent. He made the gift, it declared in language he had obviously dictated: “in consideration of the natural love and affection he has unto his daughter, Grace C. Fisher.”

On the lot, around 1840, Fisher and Grace built the largest and finest house in Edgartown: a Greek revival mansion designed by an architect said to be from Boston. Recalling stories told to him about the house’s construction, historian (and Fisher grandson) Henry Franklin Norton stated in 1940 that brass and copper fasteners were used throughout in order to forestall rust, and every timber soaked in lye to prevent rot. What the neighbors thought went unrecorded. The Vineyard Gazette would not be founded for another six years, and grievances about undue extravagance – if there were any – were aired over backyard fences rather than in letters to the editor.

The house on Main Street provided ample room for Fisher, Grace, and their three children: Daniel Jr. (1830), David (1832), and Anna (1834), along with three more born after it was built. The three younger Fishers – Elizabeth (1844), Leroy (1850), and Grace (1853) – likely played in its rooms first with same-aged cousins (children of their mother’s brother, Henry Allen Coffin) and then with Daniel Jr.’s own children, born around the same time as little Grace. The exuberant chaos generated by small children in large numbers was, however, periodically stilled. The Fishers’ first grandson, Warren (1855), died at the age of three months, and their own seventh child, Carrie (1858), succumbed to tuberculosis around the same age.

Their son Leroy’s name was a reminder of another, earlier tragedy. Dr. Leroy M. Yale – a fellow graduate of Harvard Medical School who found himself drawn to the Island – had taken over Fisher’s practice in Holmes Hole. The two had become close friends, and Yale’s medical diary shows that he periodically called on Fisher to assist him with difficult cases. In 1847, however, Yale boarded a ship in Holmes Hole Harbor that had reported illness spreading among its passengers. To the horror of Holmes Hole residents, Yale himself was stricken by it. There were at least five other physicians practicing on the Island at the time, and Fisher himself had not practiced regularly in years. He had a comfortable life, a family to provide for, and every reason not to go. That he did go – risking his own life to attend the bedside of his dying friend – suggests that there was more to Fisher than ingenuity and entrepreneurial zeal.

The year of Leroy Yale Fisher’s birth, 1850, was also the year that Fisher was persuaded to enter politics. He competed that year for the House of Representatives seat representing the Massachusetts 10th District, which at the time included the Cape and Islands. A member of the Whig party, representing its pro-business northern wing, he lost the nomination and the seat to Barnstable attorney Zeno Scudder, who successfully defended it in 1852. Fisher was named a delegate to the Whig convention in that presidential election year, when after fifty-three grueling rounds of balloting the party rejected its own incumbent president, Millard Fillmore of New York, in favor of Virginia-born General Winfield Scott, a hero of the Mexican-American War. The choice reflected the triumph of the party’s pro-slavery southern wing over the northern faction represented by Fisher, and it proved disastrous. Scott was obliterated in the general election by the handsome but undistinguished Franklin Pierce, who carried twenty-seven of thirty-one states. The Whigs were finished as a party and so was Fisher’s political career, a fact confirmed by a second defeat in an 1860 bid for Congress.

The electoral defeats must have stung, but they mattered little to his prospects on the Island. The golden age of offshore whaling was at its peak, Edgartown Harbor was busy with ships, and business was good. The 1850 federal census revealed that he was the wealthiest man on Martha’s Vineyard, and the 1860 census confirmed the honor. When the Martha’s Vineyard National Bank was formed in 1865, he was recruited to sit on its board of directors and named its first president. His name was on a wharf, a cluster of waterfront buildings, and a curious compound on Upper Main Street, where the Dukes County Jail stands today. Surrounded by a high stockade fence and guarded around the clock by a watchman, it was known to locals as “Fisher’s Fort.” Behind the fence were stacked barrels and barrels of refined whale oil – as many as 28,000 at one time – ready for sale and shipment: unimaginable wealth in tawny, liquid form.

The whaling industry had, by 1860, burned as bright as a sperm-oil lamp for forty years. On the eve of the Civil War, as the forces that had torn apart the Whigs in 1850 began to tear apart the nation, its brightness was just beginning to flicker. Whales remained plentiful, but sperm whales were growing noticeably scarcer; ships were sailing farther, and staying out longer, in order to fill their holds. Some whalers – Nantucketers in particular – had long disdained to hunt anything but sperm whales, but such selectivity was growing untenable. The quantity of sperm oil brought home by successful voyages was, increasingly, measured in hundreds, rather than thousands, of barrels. The war and depredations on the whaling fleet by Confederate ships would make matters worse; the postwar rise of the petroleum industry would in time cut the bottom out of the whale oil market.

Fisher may well have noticed, by 1860, a softness in the market that had not been there before. Whether for that reason, or simply by instinct, he spent the years during and after the war diversifying. He bought a mill in North Tisbury and began assembling farmland surrounding it. By the time he died, his holdings in what is now West Tisbury totaled nearly 600 acres. The motive for his move into agriculture was, once again, vertical integration. Why import flour (grown and milled by someone else) to supply the hardtack bakery on the Edgartown waterfront if he could develop his own supply? Dissatisfied with the lack of a direct route from Edgartown to his fields and mill in North Tisbury, he had one built.

Unlike his whale oil business, Fisher’s grain business did not thrive. The land yielded wheat, but not enough wheat to meet the demands of the bakery, and the need for imported supplies continued. The business reasoning behind the venture was sound, however, even if its agricultural realities failed to meet expectations. He retained the land until his death, and the remains of his wagon track to North Tisbury are, even today, visible to those who know where to look. Marked on maps by a fine dashed line, it is listed among the Island’s “ancient ways,” still designated by its old name: Doctor Fisher’s Road.

The stark, inescapable fact of their mortality was never far from the thoughts of nineteenth-century Americans. It was, by the mid-1860s, on Fisher’s mind as well. He had seen his share of untimely death in his practice and his personal life, and was, increasingly, contemplating his own. Writing to his son Leroy (then sixteen) in 1866, he urged the boy to “be diligent and endeavor to learn” and to avoid wasting time on frivolous pursuits like hunting, remembering that “your time is not of much consequence except to prepare you for later life.” Then, speaking with a directness that jars modern ears, he concluded: “My ‘Sands’ have nearly run and a few years more and you will have no parents to look after you and no parental roof to flee to. It will be a great gratification to your parents for you to get an education and be prepared when left to yourself and own resources to be able to go out into the world prepared to take care of yourself.”

The “sands of time” that Fisher alluded to ran more slowly than he anticipated. He lived another decade, succumbing to “dry gangrene” eight days before Christmas of 1876. He had, by that time, outlived his eldest son and namesake by nine years, and his wife by nearly six. He had lived to see the nation celebrate its centennial, and his eldest granddaughters, Emma and Clara, marry. He had also lived to see the offshore whaling fleet fall into steep decline: the victim of war, Arctic ice, and cheap petroleum. Two years before his death, in October 1874, he sold “a certain parcel of land” in Edgartown to the County of Dukes County. It was, internal evidence suggests, the site of Fisher’s Fort: once vital, now obsolete. The Gazette eulogized him as “faithful to right and to duty, and possessed [of] a clear and independent mind. He leaves behind him a respectable fortune, not one mill of which was dishonestly obtained.”

“Respectable fortune” was an understatement. The estate that Fisher bequeathed to his heirs included hundreds of acres of farmland, dozens of buildings and businesses, shares in the bank, the wharf, the Main Street mansion, and $50,000 in government bonds. Following his death, in accordance with his wishes, his surviving children divided up and liquidated much of the property. The records of the resulting land transactions take up nearly three full pages in the record books of the Dukes County Registry of Deeds. The mansion remained in the family for another decade, but in the summer of 1886, a notice in the Gazette declared that it was being placed on the market “at an enormous sacrifice.” The listing declared it to be a “large, substantial, square Mansion house, stable and grounds...well supplied with open fire-places...built regardless of cost by the late Dr. Daniel Fisher.” It was, buyers were assured, “in the most perfect condition, and needs not the outlay of a dollar.”

On January 18, 1890, Fisher’s heirs sold the wharf that had borne his name to the New Bedford, Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Steamboat Company. It was, like his acquisition of the wharf in the 1830s, a prescient decision. Whaling was long dead in Edgartown, the last ships sold or broken up for their timber and fittings. The future of Edgartown lay in serving the needs of tourists, and of the “summer people” who were buying up the old captains’ houses on Water Street. The steamship company served that market and proposed to make Edgartown a stop on its Woods Hole–to–Nantucket service. The Kelley House benefitted from its proximity to the new steamer wharf, as did the Harbor View Hotel, which opened the following summer on Starbuck Neck. The Colonial Inn, which opened in 1911, completed the trio of waterfront hotels – and Edgartown’s symbolic transformation from whaling town to summer resort.

The buyers of the big house on Main Street were two such “summer people”: Senator William Morgan Butler and his new bride, Minnie Ford Norton, daughter of an Edgartown whaling captain. Butler, the son of a Methodist minister who had preached at the camp meetings in Oak Bluffs, had loved the Island since boyhood. A prominent businessman, lawyer, and politician, he made substantial renovations to the house: adding the covered “coach entrance” on the west side and the semi-circular porch on the east side, expanding the gardens, and tearing down the stables that once stood at the rear of the property. What we think of today as the Dr. Daniel Fisher House could, in an architectural sense, just as accurately be called the William Butler House. Spiritually, however, it will always be the Fisher house, and this is as it should be. It stands shoulder to shoulder with two other whaling-era landmarks: the Old Whaling Church, built in 1843, and the Dukes County Courthouse, built in 1858. All three are expressions of pride, and acknowledgements of a great distance traveled in a very short time. The whaling

industry made Fisher, just as surely as it made Edgartown.