The first time Angie Lyon had a drink, she was twelve. Raised by two non-drinkers (one a recovering alcoholic), she raided a friend’s parents’ liquor stash while at a sleepover. At fifteen, she was regularly sneaking out of the house and lying to her parents, falling asleep in class, or ditching school altogether. Her legal troubles began at sixteen, a string of OUIs and related charges that followed her into her twenties. By the time she moved to Martha’s Vineyard, at twenty-five, she had managed to finish college and was making a good living working in retail and in restaurants. She was also a full-blown alcoholic.

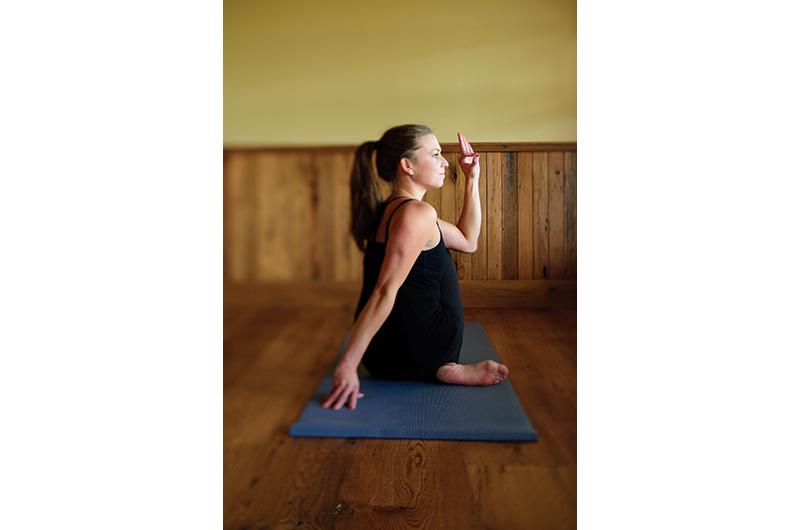

“I drank every day, all day,” Lyon said when we met at an Edgartown coffee shop one day last spring. Now thirty-two, she had come straight from a yoga class and wore a uniform familiar to many young women the Island over: leggings, a light fleece, a hint of mascara. “For me, it wasn’t about a glass of wine with dinner. It was a bottle of wine, and then we go to dinner. I had to be toasted before we got there.”

Like many young people who land on Martha’s Vineyard during or shortly after college, Lyon was drawn to the lively summer scene of hospitality work and gradually began extending her seasons until she found herself living here year-round. She shuffled from winter rental to winter rental, and despite her degree in business struggled to find a full-time job. She stuck to serving and bartending, and for a few years was able to manage her drinking, perhaps by disguising it as an occupational hazard.

“It was part of my lifestyle. It was part of my life’s design,” she said of the social drinking that ultimately escalated into a destructive daily habit and grew to include abuse of prescription painkillers like morphine and oxycodone.

Today, Lyon has been sober two years. She credits this major lifestyle change to many factors, but none more so than the Recovery Coaching Program, a fledgling peer mentorship initiative run by Martha’s Vineyard Community Services (MVCS).

According to Eric Adams, who has a professional background in counseling and has been the supervisor of the Recovery Coaching Program since its introduction to the Island in 2016, young adults struggling with substance use disorder can be a particularly hard demographic to reach. This is due to the lack of an organized framework through which to engage young adults, and also to skepticism expressed by many young people when approached with the option of traditional 12-step recovery groups.

“A lot of them are like, ‘Don’t even talk to me about AA [Alcoholics Anonymous]. What else you got?’” said Brian Morris, who oversees the recovery coaches and was one of the program’s first trained coaches. “So it was up to us to figure out, well, what else do we got?”

Lyon was a case in point. The day she met Morris and Adams at MVCS she was halfway through a regular session with her therapist, a counselor she had been seeing since arriving on the Island a few years before, when she felt the weight of her situation bearing down with a sudden, overwhelming force. Fighting a variety of legal battles while struggling to find stable housing and remain employed, she had been drinking more than ever and unable to see a way out.

“I was drowning in booze and I wasn’t telling anyone,” she said. “I was in my therapist’s office, and I had been lying to her, and I finally unloaded everything that was going on. And she said, ‘You need more help.’”

The counselor walked her immediately next door to Morris’s office, where Lyon admitted she needed support, but not without some resistance. “I really let him have it,” she remembered. “I had been drinking that day, for sure, and I was really cranky.”

She was especially reluctant to agree to a 12-step program, which she assumed would be Morris’s first line of attack. Much to her surprise, neither Morris nor his supervisor Adams suggested a program of any kind. Instead, they told her they would pair her with a female coach (participants are routinely matched by gender) and take it from there. As the program was then in its infancy, however, the only female coach was still in training, and Morris offered his services in the interim.

“Brian gave me his phone number and would text me every day. That was huge. I didn’t have that anywhere else, someone I had been honest with about my drinking who was touching base with me,” Lyon said.

“The program is based on the idea that there are multiple pathways to recovery,” said Adams. “I don’t want to bash any other approaches, but some are one-size-fits-all and I’ve heard people say things like: ‘If I wasn’t staying clean then I was doing something wrong.’ There was this idea if you just pound that square peg into a round hole long enough it will fit.”

Recovery coaching sessions can take the form of informal meetings at coffee shops, phone calls, or texts for a total of seven hours of support each week. Together, coaches and participants develop “wellness plans,” which can include traditional treatment options like group meetings, counseling, or medication, as well as more holistic approaches, such as yoga, meditation, and nutritional support. While 12-step “sponsors” offer invaluable peer support, recovery coaches are trained to be “resource brokers,” and the program is designed to provide comprehensive life support, including but not limited to helping participants forge individualized paths to sobriety.

In order to broaden the treatment options available to Islanders in recovery, MVCS has introduced two new recovery modalities to the community: Refuge Recovery, a mindfulness-based recovery program based on Buddhist principles, and SMART Recovery, a cognitive and behavioral-based approach. These programs operate in group settings, much like traditional 12-step meetings, but without the prescribed format and spiritual rhetoric that some young people have found off-putting.

Lyon’s wariness toward AA wasn’t rooted in opposition to the program’s perceived spiritual undertones. She simply didn’t see the point. “A group of people sitting around talking about the one thing I couldn’t have sounded horrible,” she remembered, comparing the experience of quitting drinking to breaking up with a boyfriend. “It didn’t make any sense.”

Until it did. When her coach finally convinced her to give the meetings a shot, she was surprised to find that the sense of community and support was exactly what she had been looking for on the Island. “Everyone is just so happy that you want to get your life back on track,” she said of the friends she’s made at the AA and Narcotics Anonymous (NA) meetings she still attends at least once, and sometimes twice, each day. “It’s a bunch of people coming together and unlocking these questions we have about ourselves, and benefiting from each other’s strengths. It’s incredible.”

While the goal of recovery coaching is not to shuttle every participant into a 12-step program, both Adams and Morris recognize the benefits of the traditional model and hope that, perhaps once seen through the lens of a recovery coach, younger generations will be more open to eventually seeking this and other roads to support.

For her part, Lyon has noticed more and more younger people at her meetings, and was surprised to find so many people in situations similar to her own. “I think the scale is tipping towards more young people coming in,” she said. “It’s okay to want to be healthy. That’s how I had to look at it.”

The Recovery Coaching Program is free, thanks to funding in part by the state Department of Public Health, and though most participants commit to three to six months, Adams is hopeful that opening lines of communication between younger generations and community service providers will have lasting effects. He calls it “planting a seed,” and it’s the same work being done at younger and younger ages within the school system.

The seed took for Lyon. Now, in addition to owning her own home organization business, she has also completed yoga teacher training. She teaches a number of yoga classes at Island studios, including one especially for people in recovery. And at the encouragement of her coaches, she has completed a recovery coach training series and was hired in March as part of the second wave of coaches brought on by Adams and MVCS. She’s one of twelve part-time coaches now on the team; in the two years that the program has been in operation about 200 clients have participated.

“I always thought that I wanted to help people in some way, but when I was drinking it just made me so sad,” she said when we reconnected recently. “To be a yoga teacher, or a recovery coach, it all seemed like such a distant dream. Now it feels so natural.”

Remembering back to the time she spent consumed by addiction, Lyon now seems awed by how much her life and perspective have changed. “I would have never in a billion years asked for help,” she said. “I don’t like to feel defeated. You have to be vulnerable. You have to be humble.

“I didn’t think people cared about me or had the resources or the time to want to help me,” she said, remembering how overwhelmed she’d felt by the amount of support she received so quickly from Adams, Morris, and eventually from her recovery coach. “I learned a lot going into this because, boy, did they care about me right away.”

1 comment

1 comment

Comments (1)