It must have been accumulating for months, the heap of trash in front of the house just around the bend from my place, but I didn’t notice. I knew that the owner of the little cottage, a very old man, had died, and I could see that someone was living there – a couple of pick-up trucks were parked in the driveway and lights were on in the house in the evenings. Renters? New owners? “I’m their neighbor, I should introduce myself,” I’d think when I drove by.

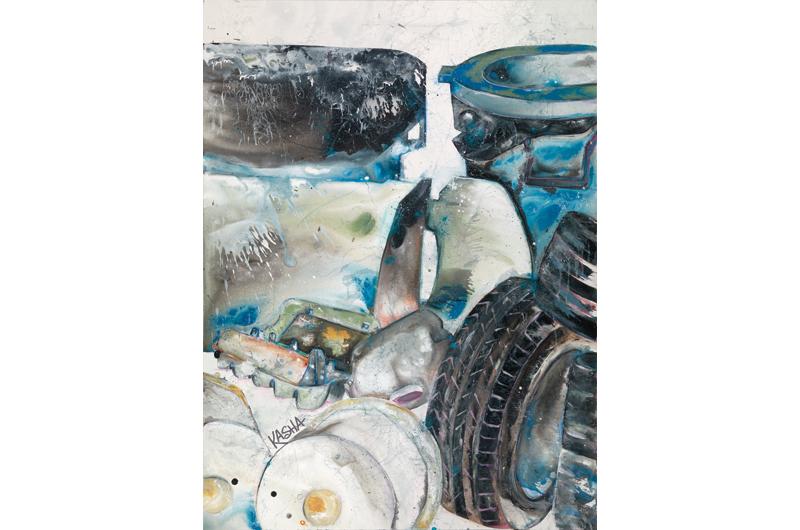

And then, one spring day, there it was: an incredible profusion of junk. The house sat close to the road with only a patch of front lawn, but the lawn was now buried in trash; not only that, the stuff spilled into the driveway and came right to the road. Four or five garbage cans, some upright and overflowing, some on their sides with empty cereal boxes and juice cartons spilling out. Plastic buckets strewn around, a clump of worn-out tires, many plastic milk jugs. Egg cartons, a roll of chicken wire, an upended rusty Weber grill. A beat-up plastic dog crate tossed on top of a tumble of logs.

So much junk. So, so much. No food scraps, no banana peels, no perishables – whoever lived in the house seemed to know about raccoons and skunks and rats – but that was all that was missing. It was as if a garbage truck had backed up to the front yard and the driver had called out to his team, “Okay, boys, let ’er rip!” and out it had all tumbled.

“Whoa,” I thought, “who are these people?” By that I didn’t mean, “How dare these people do this to the neighborhood?” I’m not sure why I didn’t, but I think it had to do with feeling more intrigued than annoyed. For one thing, I felt some kinship with them. Who among us doesn’t have a little outdoor chamber of horrors somewhere on their property, that place – behind the tool shed, or that little gulley beyond the backyard, the place nobody can see – where busted old mattress frames and porch gliders and toaster ovens go to die, while we pretend we’re going to borrow a friend’s pick-up truck next Saturday for sure and get them to the Edgartown dump. Who doesn’t imagine that one day they’ll slide down some slippery slope of not giving a rip what the neighbors think, look at that banged-up old bicycle or leaky rowboat slumped against the garage, mutter, “Oh, the hell with it,” and just leave it there forever?

For another thing, the mess was so extreme that I couldn’t believe whoever lived inside would last long in the house. They’d go broke or crazy, if they weren’t already, and disappear in the night, and some new owner would haul off the trash, and that would be the end of it. I knew that a neighbor had gone to the town hall and complained, but it seemed to me that sooner or later, probably sooner, the problem would take care of itself.

I was fascinated. I felt that slippery slope connection, but these people hadn’t just slipped down it, they’d schussed it, all the way to the bottom, and then flown off into some other, truly loopy realm. Depression, or laziness, might account for tossing a few things in your front yard, but I had to hand it to these folks: this accumulation was so brazen, so purposeful, almost like a project.

Maybe they were hoarders, only a new breed of hoarder, the exhibitionist hoarder: why hide your junk treasures indoors when you could display them, flaunt them, right out front, for all the world to see?

Maybe they were an artists’ collective, and the front yard – Le Debris – was their masterstroke.

“Jonah, I’m loving what you did with the soggy cardboard microwave box, but I wonder if we don’t need a few terra cotta flower pot shards scattered right in front of it for, you know, texture,” one member was saying to another, gazing out the window at the stuff outside.

“I’m already on it, Keith!”

“Good going, guy! Great minds, Jonah, great minds.”

Maybe they were an anarchist cell, making a statement about consumerism. Maybe they were members of a religious cult, building a trash mountain to Heaven, planning a nutty collective leap onto the next crescent moon. I doubted it, but I’d always wanted to observe a cult up close, and I had my hopes up.

I asked around and learned the occupants were a couple, a young man and woman who’d left a city to come and live here. They were renting the house from an absentee landlord, a relative of the old man who’d died. The couple was in business together, and their business involved clearing people’s properties of unwanted brush and invasive weeds.

No cult, alas, but this information was almost as tantalizing: these were people who cleared people’s properties for a living. How could this be?

And they seemed to be fully employed – prospering, even. As the weeks went by, more pick-up trucks were parked in the driveway and wedged in along the curb, sometimes three or four at a time. One day a brand-new, shiny silver pick-up truck joined the crowd and I found myself thinking, meanly, “Wait a minute, they don’t deserve this. Ma, I did all my chores and they didn’t do any! Why do they get a new toy? It’s not fair!”

More weeks went by. Spring turned to summer. The mass of junk grew by the day, or seemed to. A toppled-over old propane tank. Empty coffee cans. A clump of wire hangers. More heaps of firewood, some tangled cables drooping over other piles of other stuff. A vacuum cleaner hose, lying on the lawn like a dead boa constrictor. Another truck, only this one ancient and battered and clearly not going anywhere.

I was – there’s no other word for it – stalking the property. I’d started taking walks down the road, pretending to be on an afternoon stroll, just to look at it. I’d stop at the house and look up at the sky, pretending to be seeing an interesting cloud formation or a hawk’s slow swoops above while stealing glances at all the stuff, noting new additions, hoping for a clue to the people who lived inside. I couldn’t find any. Apart from being very fond of milk – so many milk jugs! – they remained a mystery.

What I really wanted was to see them. I’d say a cheery “Hello!”, introduce myself, and take their measure, depending on what happened next. Maybe they’d say hello back and I could engage them in conversation; maybe they’d ignore me, slink into one of their trucks, and peel off. But no one ever appeared. That, and the fact that most of the trucks seemed to be gone during the day, suggested that they were out working. At their job making people’s properties look lovely.

A neighbor told me that before the lawn had become an eyesore (that’s what the neighbor who complained about it was told at the town hall – the accumulation was an “eyesore,” and legally there was nothing to do as it was their property, and they could do what they wanted with it) she’d thought about hiring them. The young man had even come to see her to assess the work to be done. “What was he like, what was he like, what was he like?”, I asked.

“Oh, just very pleasant. Nice-looking.”

“Did he seem, you know, crazy in any way?”

“Not at all. I would’ve hired him, but it was just going to be too expensive.”

Nice-looking. Pleasant. These were not adjectives that helped me. They were not going to explain why the couple had turned their front yard into their own personal dump. Clearly, I would have to do further research.

So I called them. Their phone number was on their website – which was well-designed, with beautiful photographs, and which deepened the mystery; I expected no website at all, or something upside down, or handwritten in a strange, illegible scrawl. I left a message: “I’m interested in your services, please call me back.”

It was deception, plain and simple. I had no intention of hiring them.

I felt bad about it. Not so bad that I didn’t do it, but bad. Bad enough that I regretted it as soon as I’d left the message. “Don’t call back,” I found myself thinking, over and over.

And, as often happens when you’ve done a bad thing, other bad things start dancing around in your head. Like: I’d done just the kind of thing, the kind of un-neighorborly thing, that had made me glad to leave, a couple of years earlier, the apartment building in New York where I’d raised my kids. We’d had some wonderful neighbors in the building, but we had some awful ones, too – which, like thousands of other apartment buildings in Manhattan, had gone from a rental into a co-op in the seventies. Increasingly affluent residents would renovate at all hours and illegally (forbidden jackhammers! On weekends!), deaf to the complaints of their victims below. Board members, meanwhile, responded to our voiced complaints at annual meetings not at all, instead announcing plans to renovate the lobby yet again.

The couple had amassed an eyesore and that wasn’t a thoughtful thing to do, but really, who was worse – the slobs or the snoop?

They never called back. “Good for you,” I thought.

Then, one day, they were gone. No trucks, no trash, nothing. Just the little house, dark now, and a pristine lawn, and an empty driveway.

It was good to see all that order. But I had to admit it: I felt…disappointed. The property was so much more interesting with all that stuff. It had been my entertainment; it had intrigued me for many months. And now I’d never solve my little mystery about who lived inside.

But even if I had found out – had discovered, say, that they believed, insanely, that the front yard was where you were supposed to put your garbage (“We hang out in the backyard – no way we’re going to put our junk there!”) – what was I going to do with that information? Gossip about them? Turn them into a story to entertain my friends?

And whom would that serve?

Really, would it have killed me to go over there when I first saw those lights on in the house and say hello? “Welcome to the neighborhood,” I could have said. Would it have made a difference? Would they have said to each other, “Say, let’s think of the nice lady around the bend and, oh, I don’t know, take our trash to the dump”? Probably not. But it would have been a nice thing to do.

I could have, but I didn’t. And that, as the kids say, is on me.