Allen Whiting is tired of talking about himself.

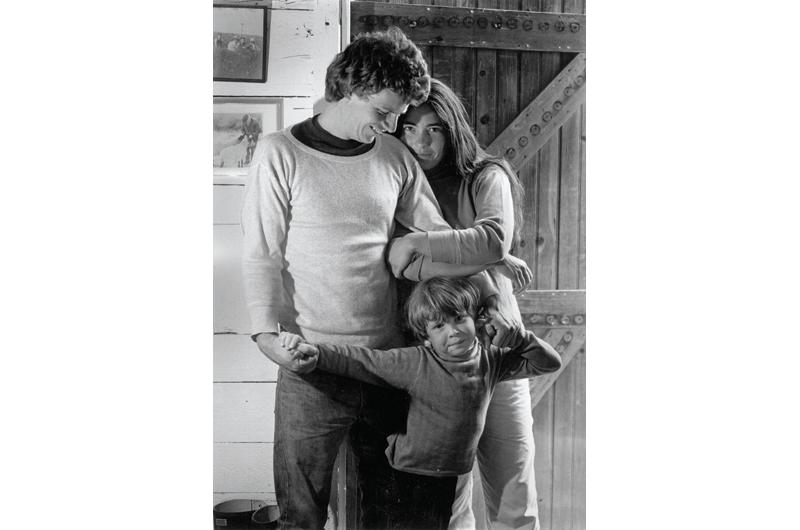

“The biographical stuff about me doesn’t matter anymore,” he said as we sat in his kitchen talking about, among other things, the fact that somehow he’s seventy, about to turn seventy-one, and it’s been thirty-five years already that he and his wife, Lynne, have been showing and selling his instantly recognizable landscape paintings out of the front rooms of their farmhouse in West Tisbury.

It was one of those relentlessly rainy days in what felt at times like a relentlessly rainy spring, and Whiting was distracted, staring through a side door at the heavy drops splashing into the deep puddles in the driveway. Distracted may not be the right word. Whiting is deliberate with his attentions; as a man with at least three full-time professions, he would have to be. In addition to painting and running the gallery with his wife, Whiting is a farmer and a property manager – he inherited the Whiting farm and all of its various outbuildings – and he is dedicated to each role in equal measure.

“Local boy does good,” he joked, speaking in italics, playfully mocking his own backstory by distilling it down to four words. After nearly five decades of painting the land his family has owned and farmed for generations, he’s given countless interviews and garnered an impressive roster of accolades and titles. In print, he’s been called everything from a “Landscape Master” to the “Island’s Son,” and it’s safe to say he has earned both his place in the pantheon of esteemed Vineyard artists – and the right to remain silent.

As it happens, though, there remains a long list of things that Whiting is not tired of talking about: painting, of course, and his family; Martha’s Vineyard, past and present; his patrons; his gallery; his friends; his farm and houses and the maintenance each requires; trees; tractors; pigs; the color of the dress his wife was wearing on the day they met…

Whiting’s biography has been well-documented – and will be re-documented in part here, with apologies – not because family history is inherently relevant to any painter’s trajectory, but because it is inextricably linked to the lens through which this particular artist views and interprets his surroundings. It’s not so much the heavyweight lineage – a Whiting family tree includes enough Mayhews, Looks, and Bradfords to settle a second island – as it is the combination of a deep sense of connection to the land and an inherited artist’s eye.

Whiting’s maternal grandfather, Percy Cowen, was a professional illustrator and accomplished painter – family legend has it that Cowen and the American Regionalist Thomas Hart Benton often painted on the Menemsha docks together. At the time, Benton was newly arrived on the Island by way of Paris and hadn’t yet settled on capturing the scenes and landscapes that would go on to define his career. “It’s easy to make a connection that maybe he got Benton excited about painting rural America,” Whiting said of his grandfather. “I only met Benton once and I was too stupid to ask him.”

Though Cowen died young – from an infection after returning home from World War I – he had a lasting influence on Whiting. “I’ve always loved my grandfather’s paintings,” he said of the mostly figurative works he grew up admiring, many of which still hang in the halls of his home today. “That’s what got me going, but it also kept me from working for a long time. They were intimidating to me.”

Later, when Whiting began painting with friend Bill McLane, the pair would often bring out a piece of Cowen’s work, keeping it near them while they tinkered with their own, “as a corrective.”

“We called him the better painter,” Whiting said. “I wish he’d lived. I wish I’d known him.”

Not knowing his grandfather, perhaps, added an air of impossibility to the notion of painting as a profession. Growing up on the farm, art wasn’t something that was discussed much or encouraged, and when Whiting left college in Florida he didn’t think twice about coming home to work the same fields he’d helped care for as a kid. It wasn’t until years later that he visited his first museum, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, and felt called to follow in his grandfather’s footsteps.

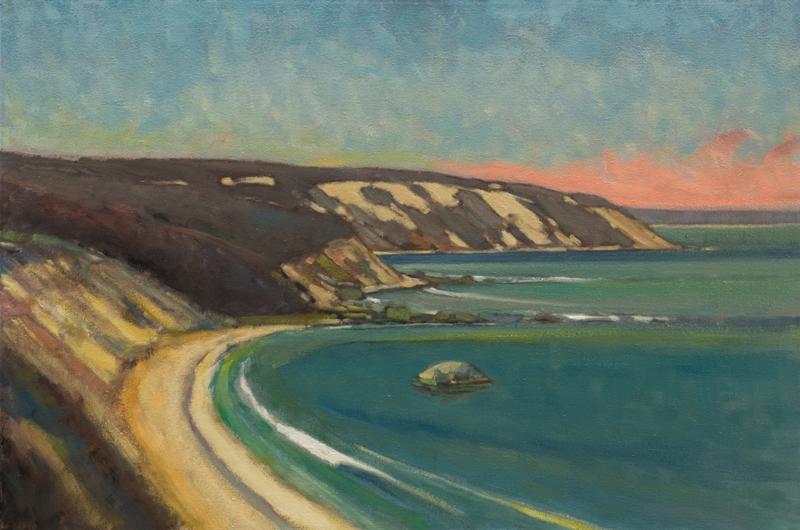

But long before it was his profession, an artist’s spirit was deeply woven into Whiting’s approach to everything – even the most mundane of farm chores. “I remember being ten years old and driving down near Quansoo with my father, and seeing the tree line descend down the field towards the ocean,” Whiting recalled. “I just knew at that point that there was something in that tree line for me. I didn’t know what it was. But I remember that vision, and I’m still painting that tree line today.”

Boundaries of time and place, of family and art and life, are further blurred every summer when he and Lynne transform their home into a gallery for Whiting’s work. Chris Morse at the Granary Gallery in West Tisbury handles secondary sales and some site-specific commissions. Otherwise, Whiting’s home is one of the only places in the world to buy an original Allen Whiting painting. The decision to forego the traditional gallery model was made early on, and it’s one that the Whitings attribute less to savvy business sense and more to good luck and timing. After a few years of successful shows at the Field Gallery in West Tisbury, Whiting knew he had to take things up a notch. “I was thirty-five and at my last show, I made $10,000,” Whiting remembered. “And I had to give the gallery a third.”

After Whiting’s father died in 1981, he inherited the Davis House, a family property in West Tisbury. (The house takes its name from Whiting’s great uncle Everett Allen Davis, who built it in the 1870s.) Whiting and Lynne began to talk about turning a few rooms into a showcase of their own. Not only did they have the space, but the location, steps from the heart of West Tisbury, wasn’t bad, either. “Most people aren’t as lucky to inherit a lovely Victorian home on the side of State Road,” Whiting allowed.

“We thought what we needed to do was replicate the sparse gallery scene,” Lynne remembered. They painted the walls stark white and removed all of the furniture. But they quickly realized that people felt more comfortable in the gallery the more it felt like home. Today, at the beginning of the season, some furniture is rearranged – their grandson’s toys tucked away – but for the most part, visitors are given a real glimpse into the artist’s family home. Lynne said occasionally she finds people wandering into corners, perusing her collection of books. “I’ll think, ‘I guess I’d better dust the shelves,’” she said.

“It was during that great expansive time on the Island,” Whiting said of the Davis House Gallery’s early days, when things were simple and business was booming. “I loved it. Some people hate the idea that anybody found us, but I thought it was pretty cool. People loved where we lived.”

With some small allowance for talent (“I guess if they really hated my work they wouldn’t have bought it”), Whiting believes the reason he found such early success was that he was painting the Island at the very time people were most wanting a piece of it. “Luckily, my passion was painting the Vineyard, which was drawing everybody here anyway,” he said.

With a gallery in his living room each summer, Whiting’s family naturally played a major role in the daily operations. Their daughter, Beatrice (Bea), was a toddler when the gallery opened; son Everett was weeks old. (Whiting has another son, Will, from a previous marriage.) “When I first learned to write my name I would write it on every page of the guest book,” Bea remembered. As an older child, she’d follow her father from painting to painting, helping to name each one. Later still, she became the gallery manager, and Lynne and Allen credit her with bringing the business into the twenty-first century, adding an online presence and encouraging them to publish a book, Allen Whiting: A Painter at Sixty. Now a nurse at the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital and a mother of two, she has less time but

remains involved as her schedule allows. “My parents and I were a good team,” she said. “We still are.”

As the years went on, Whiting’s following grew, and the now-legendary summer opening parties were born. These annual gatherings started small, as a way to introduce the last winter’s crop of paintings, but quickly turned into lavish affairs, with local catered food (often provided by their son, Everett, a chef) and live music, until the stress of preparations and crowd control grew to be too much.

“The openings just got too big,” Whiting said. “There was such a boom here in the early 2000s. The rock stars were coming; the politicians were coming. It got out of hand.”

When the commotion of the parties began to encroach on Whiting’s carefully maintained equilibrium – the balance of family, painting, and the farm – he and Lynne decided to take a break. “As much as I felt flattered by it, there were times when we ended up getting in family knots. And that’s what I hated,” he said. “I said, ‘If this is being done for me, let’s forget it.’”

And so, for a few years, the Whitings decided to forego their annual fête, instead opting to focus on special projects – a 2011 retrospective at Featherstone Center for the Arts, for example – and experimenting with different types of more intimate gallery events. But they quickly sensed that their friends and patrons felt that something was missing. “People loved coming and seeing what was new, and seeing each other,” Whiting said.

These days, the openings are quieter affairs and have more of the feel of a reunion for an extended “family” of Whiting’s lifelong fans and friends than a raucous party of young adults. “It’s sort of exactly the way it should be,” Whiting said. “A little less hubbub, and a few more serious buyers.” And the paintings are still hand-sold, as it were, the way a farmer might sell eggs or hay to the neighbors.

“Nobody that we hired ever sold any paintings,” Whiting laughed. “It was always Lynne or I. It pays to be visible. Some artists can’t stand it, but we’re social. I don’t mind talking to people and I think people appreciate it.”

With the steady flow of gallery visitors, work on the farm, and a busy social calendar, it would be fair to assume that Whiting takes a break from painting in the summer. He does not. “I can go to the studio at night some,” he shrugged, when asked how he finds the time. “I do less and less as I get older. Sometimes I like to bitch that the world gets in my way, but that’s every artist’s problem. It’s up to you to get up earlier or stay up later. If you love TV, put your easel here and your TV there. If you’re cold, put it next to the wood stove. There are always answers.”

This pragmatic workhorse approach to painting helps keep him prolific, and perhaps not as precious about the final result. “We put the concept of perfection on ourselves and there is no such thing,” he said. “It’s a sliding definition of perfection. I want the paintings to be just right, but I want them to be me, too. A copy of a photograph is not perfection to me.”

For younger generations on the Island, Whiting’s perspective on painting and the business of being an artist has been an inspiration. Max Decker, a painter and friend of Whiting’s son Everett, grew up hanging around the Whiting household and credits this exposure with much of his own development as an artist today. “There’s a good chance I would have never gotten into painting if I hadn’t been lucky enough to see the inner workings of the studio and gone to so many of their gallery shows from an early age,” Decker said.

As a teenager, Decker would accompany Whiting on painting excursions in his fields. “I learned by watching,” he recalled. “He was never overt about revealing technique. I could have used a tip or two, but ruining paintings can be illuminating.”

Decker admires Whiting’s ability to immerse himself in an environment for so long and still find ways to stay personally connected to the material – so much so that the shape and textures of the Island landscape now seem to be forever engaged in a conversation with Whiting’s interpretations of them. “When I’m out walking around I’ll see a certain tree or view and I’ll think to myself, ‘Oh, that’s a nice Allen Whiting painting.’”

For Whiting’s part, he’s eager to see how the next generation of Island painters grows and develops, and is hopeful that the home-gallery model will work for them, where available, as it has for him and his family. But most of all, disciples of the “Whiting Method” would be wise to work hard, stay out of their own way, and do only the work they love best.

“Some actor once said, ‘The camera hates acting.’ You’ve really got to be yourself. You don’t have to feel afraid,” Whiting advised. “Nor do you have to spend a lot of time with a head cramp trying to be completely original, because somebody’s probably done it anyway.”

Whiting finished the last of his coffee and looked toward the door. The rain was still falling in sheets and there were chores to be done. Lynne’s phone beeped with unread messages; plans for the summer season – and the much-anticipated return of the gallery’s opening party in June – had already begun. But after years of practice, the Whitings have found a way to take it all in stride.

Whiting will turn seventy-one at the end of July. He knows he’s not exactly “up and coming.” Nor is he, as many artists attempt to do at various points in their careers, reinventing himself in any way. He’s still Allen Whiting, and he’s still here, painting lush Island landscapes.

“You’ve just got to do what you want,” he said. “The Island is your oyster.”